CS50: Week 7 - SQL

- Welcome!

- Keyword

- Flat-File Database

- Relational Databases

- Shows

JOINs- Indexes

- Using SQL in Python

- Race Conditions

- SQL Injection Attacks

- Summing Up

Welcome!

- In previous weeks, we introduced you to Python, a high-level programming language that utilized the same building blocks we learned in C. However, we introduced this new language not for the purpose of learning “just another language.” Instead, we do so because some tools are better for some jobs and not so great for others!

- This week, we will be continuing more syntax related to Python.

- Further, we will be integrating this knowledge with data.

- Finally, we will be discussing SQL or Structured Query Language.

- Overall, one of the goals of this course is to learn to program generally – not simply how to program in the languages described in this course.

Keyword

Database Structure

- Tables: Organized collections of data.

- Types: Data types for columns (e.g., INT, VARCHAR, DATE).

- Constraints: Rules that ensure data integrity (e.g., NOT NULL, UNIQUE, PRIMARY KEY).

- Indexes: Data structures that improve query performance.

Data Manipulation

- Statements: Commands to interact with the database (e.g., SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE).

- Keywords: Reserved words used in SQL statements (e.g., WHERE, FROM, ORDER BY).

- Functions: Built-in or user-defined operations on data (e.g., SUM, AVG, COUNT).

Data Management

- Transactions: Units of work that are treated as a single unit (e.g., COMMIT, ROLLBACK).

Potential Issues

- Race Conditionals: Unintended behavior caused by concurrent access to shared data.

- SQL Injection Attacks: Security vulnerabilities where malicious SQL code is injected into an application.

Flat-File Database

- As you have likely seen before, data can often be described in patterns of columns and rows.

- Spreadsheets like those created in Microsoft Excel and Google Sheets can be outputted to a

csvor comma-separated values file. - If you look at a

csvfile, you’ll notice that the file is flat in that all of our data is stored in a single table represented by a text file. We call this form of data a flat-file database. - Python comes with native support for

csvfiles. - First, download favorites.csv rename to favorites.csv and upload it to your file explorer inside cs50.dev. Second, in your terminal window, type

code favorites.pyand write code as follows:

# Prints all favorites in CSV using csv.reader

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create reader

reader = csv.reader(file)

# Skip header row

next(reader)

# Iterate over CSV file, printing each favorite

for row in reader:

print(row[1])

Notice that the csv library is imported. Further, we created a reader that will hold the result of csv.reader(file). The csv.reader function reads each row from the file, and in our code we store the results in reader. print(row[1]), therefore, will print the language from the favorites.csv file.

- You can improve your code as follows:

# Stores favorite in a variable

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create reader

reader = csv.reader(file)

# Skip header row

next(reader)

# Iterate over CSV file, printing each favorite

for row in reader:

favorite = row[1]

print(favorite)

Notice that favorite is stored and then printed. Also notice that we use the next function to skip to the next line of our reader.

- One of the disadvantages of the above approach is that we are trusting that

row[1]is always the favorite. However, what would happen if the columns have been moved around? - We can fix this potential issue. Python also allows you to index by the keys of a list. Modify your code as follows:

# Prints all favorites in CSV using csv.DictReader

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Iterate over CSV file, printing each favorite

for row in reader:

favorite = row["language"]

print(favorite)

Notice that this example directly utilizes the language key in the print statement.

- This could be further simplified to:

# Prints all favorites in CSV using csv.DictReader

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Iterate over CSV file, printing each favorite

for row in reader:

print(row["language"])

- To count the number of favorite languages expressed in the

csvfile, we can do the following:

# Counts favorites using variables

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

scratch, c, python = 0, 0, 0

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["language"]

if favorite == "Scratch":

scratch += 1

elif favorite == "C":

c += 1

elif favorite == "Python":

python += 1

# Print counts

print(f"Scratch: {scratch}")

print(f"C: {c}")

print(f"Python: {python}")

Notice that each language is counted using if statements. Further notice the double equal == signs in those if statements.

- Python allows us to use a dictionary to count the

countsof each language. Consider the following improvement upon our code:

# Counts favorites using dictionary

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = {}

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["language"]

if favorite in counts:

counts[favorite] += 1

else:

counts[favorite] = 1

# Print counts

for favorite in counts:

print(f"{favorite}: {counts[favorite]}")

Notice that the value in counts with the key favorite is incremented when it exists already. If it does not exist, we define counts[favorite] and set it to 1. Further, the formatted string has been improved to present the counts[favorite].

- Python also allows sorting

counts. Improve your code as follows:

# Sorts favorites by key

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = {}

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["language"]

if favorite in counts:

counts[favorite] += 1

else:

counts[favorite] = 1

# Print counts

for favorite in sorted(counts):

print(f"{favorite}: {counts[favorite]}")

Notice the sorted(counts) at the bottom of the code.

- If you look at the parameters for the

sortedfunction in the Python documentation, you will find it has many built-in parameters. You can leverage some of these built-in parameters as follows:

# Sorts favorites by value using .get

import csv

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = {}

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["language"]

if favorite in counts:

counts[favorite] += 1

else:

counts[favorite] = 1

# Print counts

for favorite in sorted(counts, key=counts.get, reverse=True):

print(f"{favorite}: {counts[favorite]}")

Notice the arguments passed to sorted. The key argument allows you to tell Python the method you wish to use to sort items. In this case counts.get is used to sort by the values. reverse=True tells sorted to sort from largest to smallest.

- Python has numerous libraries that we can utilize in our code. One of these libraries is

collections, from which we can importCounter.Counterwill allow you to access the counts of each language without the headaches of all theifstatements seen in our previous code. You can implement as follows:

# Sorts favorites by value using .get

import csv

from collections import Counter

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = Counter()

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["language"]

counts[favorite] += 1

# Print counts

for favorite, count in counts.most_common():

print(f"{favorite}: {count}")

Notice how counts = Counter() enables the use of this imported Counter class from collections.

- We can change the column we are examining, focusing on our favorite problem instead:

# Favorite problem instead of favorite language

import csv

from collections import Counter

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = Counter()

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["problem"]

counts[favorite] += 1

# Print counts

for favorite, count in counts.most_common():

print(f"{favorite}: {count}")

Notice that problem replaced language.

- We can also get the count of the popularity of a specific problem in the course:

# Gets a specific count

import csv

from collections import Counter

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = Counter()

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["problem"]

counts[favorite] += 1

# Print count

favorite = input("Favorite: ")

print(f"{favorite}: {counts[favorite]}")

Notice how compact our code is compared to our experience in C.

Relational Databases

- Google, Twitter, and Meta all use relational databases to store their information at scale.

- Relational databases store data in rows and columns in structures called tables.

- SQL allows for four types of commands:

Create

Read

Update

Delete

- These four operations are affectionately called CRUD.

- We can create a SQL database at the terminal by typing

sqlite3 favorites.db. Upon being prompted, we will agree that we want to createfavorites.dbby pressingy. - You will notice a different prompt as we are now inside a program called

sqlite3. - We can put

sqlite3intocsvmode by typing.mode csv. Then, we can import our data from ourcsvfile by typing.import favorites.csv favorites. It seems that nothing has happened! - We can type

.schemato see the structure of the database. - You can read items from a table using the syntax

SELECT columns FROM table. - For example, you can type

SELECT * FROM favorites;which will iterate every row infavorites. - You can get a subset of the data using the command

SELECT language FROM favorites;. - SQL supports many commands to access data, including:

AVG

COUNT

DISTINCT

LOWER

MAX

MIN

UPPER

- For example, you can type

SELECT COUNT(language) FROM favorites;. Further, you can typeSELECT DISTINCT(language) FROM favorites;to get a list of the individual languages within the database. You could even typeSELECT COUNT(DISTINCT(language)) FROM favorites;to get a count of those. - SQL offers additional commands we can utilize in our queries:

WHERE -- adding a Boolean expression to filter our data

LIKE -- filtering responses more loosely

ORDER BY -- ordering responses

LIMIT -- limiting the number of responses

GROUP BY -- grouping responses together

Notice that we use -- to write a comment in SQL.

- For example, we can execute

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM favorites WHERE language = 'C';. A count is presented. - Further, we could type

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM favorites WHERE language = 'C' AND problem = 'Hello, World;. Notice how theANDis utilized to narrow our results. - Similarly, we could execute

SELECT language, COUNT(*) FROM favorites GROUP BY language;. This would offer a temporary table that would show the language and count. - We could improve this by typing

SELECT language, COUNT(*) FROM favorites GROUP BY language ORDER BY COUNT(*);. This will order the resulting table by thecount. - We can also

INSERTinto a SQL database utilizing the formINSERT INTO table (column...) VALUES(value, ...);. - We can execute

INSERT INTO favorites (language, problem) VALUES ('SQL', 'Fiftyville');. DELETEallows you to delete parts of your data. For example, you couldDELETE FROM favorites WHERE Timestamp IS NULL;.- We can also utilize the

UPDATEcommand to update your data. - For example, you can execute

UPDATE favorites SET language = 'SQL', problem = 'Fiftyville';. This will result in overwriting all previous statements where C was the favorite programming language. - Notice that these queries have immense power. Accordingly, in the real-world setting, you should consider who has permissions to execute certain commands.

Shows

- We can imagine a database that we might want to create to catalog various TV shows. We could create a spreadsheet with columns like

title,star,star,star,star, and more stars. A problem with this approach is this approach has a lot of wasted space. Some shows may have one star. Others may have dozens. - We could separate our database into multiple sheets. We could have a

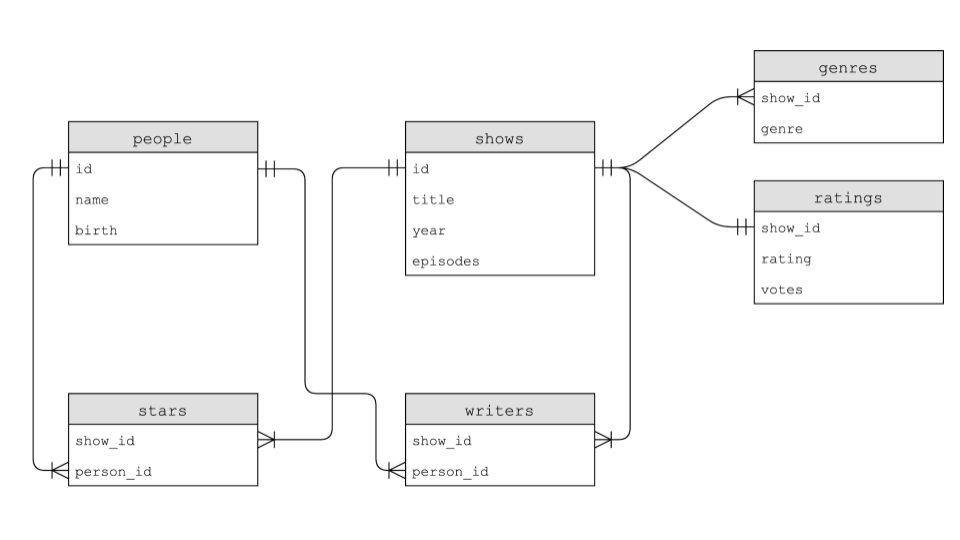

showssheet and apeoplesheet. On thepeoplesheet, each person could have a uniqueid. On theshowssheet, each show could have a uniqueidtoo. On a third sheet calledstarswe could relate how each show has people for each show by having ashow_idandperson_id. While this is an improvement, this is not an ideal database. - IMDb offers a database of people, shows, writers, stars, genres, and ratings. Each of these tables is related to one another as follows:

- After downloading

shows.db, you can executesqlite3 shows.dbin your terminal window. - Let’s zero in on the relationship between two tables within the database called

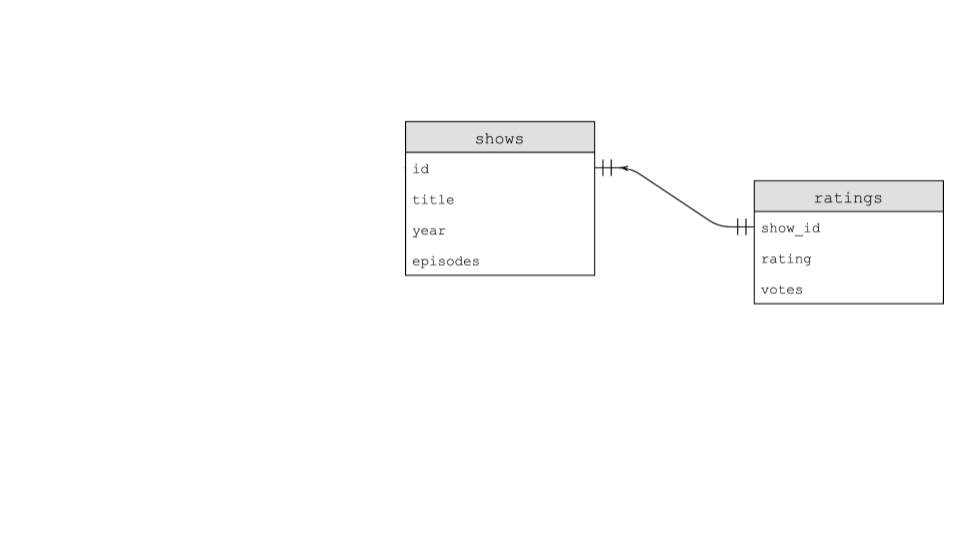

showsandratings. The relationship between these two tables can be illustrated as follows:

- To illustrate the relationship between these tables, we could execute the following command:

SELECT * FROM ratings LIMIT 10;. Examining the output, we could executeSELECT * FROM shows LIMIT 10;. - To understand the database, upon executing

.schemayou will find not only each of the tables but the individual fields inside each of these fields. - As you can see,

showshas anidfield. Thegenrestable has ashow_idfield which has data that is common between it and theshowstable. - Further,

show_idexists in all of the tables. In theshowstable, it is simply calledid. This common field between all the fields is called a key. Primary keys are used to identify a unique record in a table. Foreign keys are used to build relationships between tables by pointing to the primary key in another table. - By storing data in a relational database, as above, data can be more efficiently stored.

- In sqlite, we have five datatypes, including:

BLOB -- binary large objects that are groups of ones and zeros

INTEGER -- an integer

NUMERIC -- for numbers that are formatted specially like dates

REAL -- like a float

TEXT -- for strings and the like

-

Additionally, columns can be set to add special constraints:

-

We could execute

SELECT * FROM stars LIMIT 10;.show_idis a foreign key in this final query becauseshow_idcorresponds to the uniqueidfield inshows.person_idcorresponds to the uniqueidfield in thepeoplecolumn. -

We can further play with this data to understand these relationships. Execute

SELECT * FROM ratings;. There are a lot of ratings! -

We can further limit this data down by executing

SELECT show_id FROM ratings WHERE rating >= 6.0 LIMIT 10;. From this query, you can see that there are 10 shows presented. However, we don’t know what show eachshow_idrepresents. -

You can discover what shows these are by executing

SELECT * FROM shows WHERE id = 626124; -

We can further our query to be more efficient by executing:

SELECT title

FROM shows

WHERE id IN (

SELECT show_id

FROM ratings

WHERE rating >= 6.0

LIMIT 10

)

Notice that this query nests together two queries. An inner query is used by an outer query.

JOINs

- We are pulling data from

showsandratings. - How could we combine tables temporarily? Tables could be joined together using the

JOINcommand. - Execute the following command:

SELECT * FROM shows

JOIN ratings on shows.id = ratings.show_id

WHERE rating >= 6.0

LIMIT 10;

Notice this results in a wider table than we have previously seen.

- Where the previous queries have illustrated the one-to-one relationship between these keys, let’s examine some one-to-many relationships. Focusing on the

genrestable, execute the following:

SELECT * FROM genres

LIMIT 10;

Notice how this provides us a sense of the raw data. You might notice that one shows have three values. This is a one-to-many relationship.

- We can learn more about the

genrestable by typing.schema genres. - Execute the following command to learn more about the various comedies in the database:

SELECT title FROM shows

WHERE id IN (

SELECT show_id FROM genres

WHERE genre = 'Comedy'

LIMIT 10

);

Notice how this produces a list of comedies, including Catweazle.

- To learn more about Catweazle, by joining various tables through a join:

SELECT * FROM shows

JOIN genres

ON shows.id = genres.show_id

WHERE id = 63881;

Notice that this results in a temporary table. It is fine to have duplicate table.

- A final relationship is a many-to-many relationship.

- We can learn more about the show The Office by executing the following command:

SELECT person_id FROM stars

WHERE show_id = (

SELECT id FROM shows

WHERE title = 'The Office' AND year = 2005

);

Notice that this results in a table that includes the person_ids of various stars.

- I could learn more about this group of actors by executing the following:

SELECT name FROM people

WHERE id IN (

SELECT person_id FROM stars

WHERE show_id = (

SELECT id FROM shows

WHERE title = 'The Office' AND year = 2005

)

);

This results in a top-billed stars.

- We can further understand this data by executing:

SELECT title from shows

WHERE id IN (

SELECT show_id FROM stars

WHERE person_id = (

SELECT id FROM people

WHERE name = 'Steve Carell'

)

);

This results in a list of titles of shows wherein Steve Carell stared.

- The wildcard

%operator can be used to find all people whose names start withSteve Cone could employ the syntaxSELECT * FROM people WHERE name LIKE 'Steve C%';.

Indexes

- While relational databases have the ability to be more fast and more robust than utilizing a

CSVfile, data can be optimized within a table using indexes. - Indexes can be utilized to speed up our queries.

- We can track the speed of our queries by executing

.timer oninsqlite3. - To understand how indexes can speed up our queries, run the following:

SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = 'The Office';Notice the time that displays after the query executes. - Then, we can create an index with the syntax

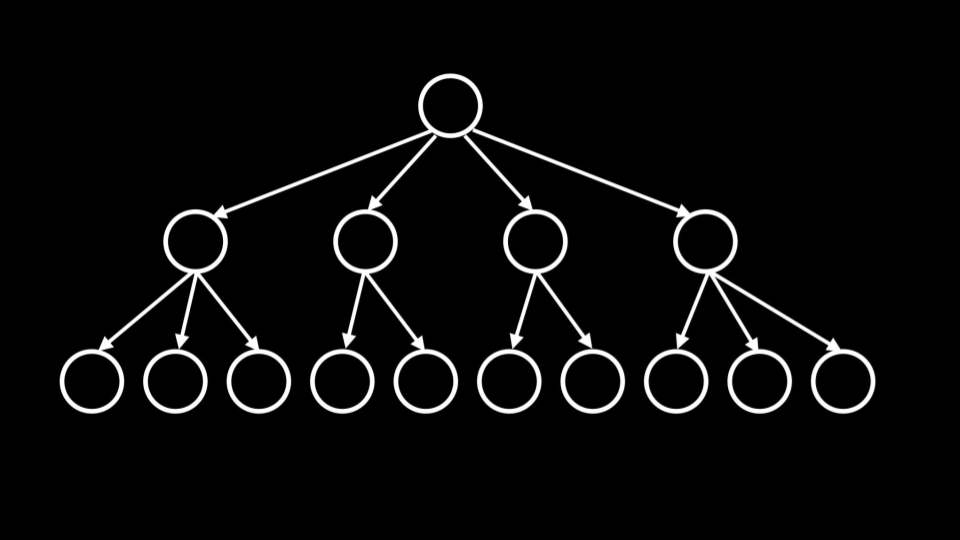

CREATE INDEX title_index on shows (title);. This tellssqlite3to create an index and perform some special under-the-hood optimization relating to this columntitle. - This will create a data structure called a B Tree, a data structure that looks similar to a binary tree. However, unlike a binary tree, there can be more than two child notes.

- Running the query

SELECT * FROM shows WHERE title = 'The Office';, you will notice that the query runs much more quickly! - Unfortunately, indexing all columns would result in utilizing more storage space. Therefore, there is a tradeoff for enhanced speed.

Using SQL in Python

-

To assist in working with SQL in this course, the CS50 Library can be utilized as follows in your code:

-

Similar to previous uses of the CS50 Library, this library will assist with the complicated steps of utilizing SQL within your Python code.

-

You can read more about the CS50 Library’s SQL functionality in the documentation.

-

Recall where we last left off in

favorites.py. Your code should appear as follows:

# Gets a specific count

import csv

from collections import Counter

# Open CSV file

with open("favorites.csv", "r") as file:

# Create DictReader

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

# Counts

counts = Counter()

# Iterate over CSV file, counting favorites

for row in reader:

favorite = row["problem"]

counts[favorite] += 1

# Print count

favorite = input("Favorite: ")

print(f"{favorite}: {counts[favorite]}")

Notice how this code is exactly as we left it prior.

- Modify your code as follows:

# Searches database popularity of a problem

import csv

from cs50 import SQL

# Open database

db = SQL("sqlite:///favorites.db")

# Prompt user for favorite

favorite = input("Favorite: ")

# Search for title

rows = db.execute("SELECT COUNT(*) AS n FROM favorites WHERE problem LIKE ?", favorite)

# Get first (and only) row

row = rows[0]

# Print popularity

print(row["n"])

Notice that db = SQL("sqlite:///favorites.db") provide Python the location of the database file. Then, the line that begins with rows executes SQL commands utilizing db.execute. Indeed, this command passes the syntax within the quotation marks to the db.execute function. We can issue any SQL command using this syntax. Further, notice that rows is returned as a list of dictionaries. In this case, there is only one result, one row, returned to the rows list as a dictionary.

Race Conditions

- Utilization of SQL can sometimes result in some problems.

- You can imagine a case where multiple users could be accessing the same database and executing commands at the same time.

- This could result in glitches where code is interrupted by other people’s actions. This could result in a loss of data.

- Built-in SQL features such as

BEGIN TRANSACTION,COMMIT, andROLLBACKhelp avoid some of these race condition problems.

SQL Injection Attacks

- Now, still considering the code above, you might be wondering what the

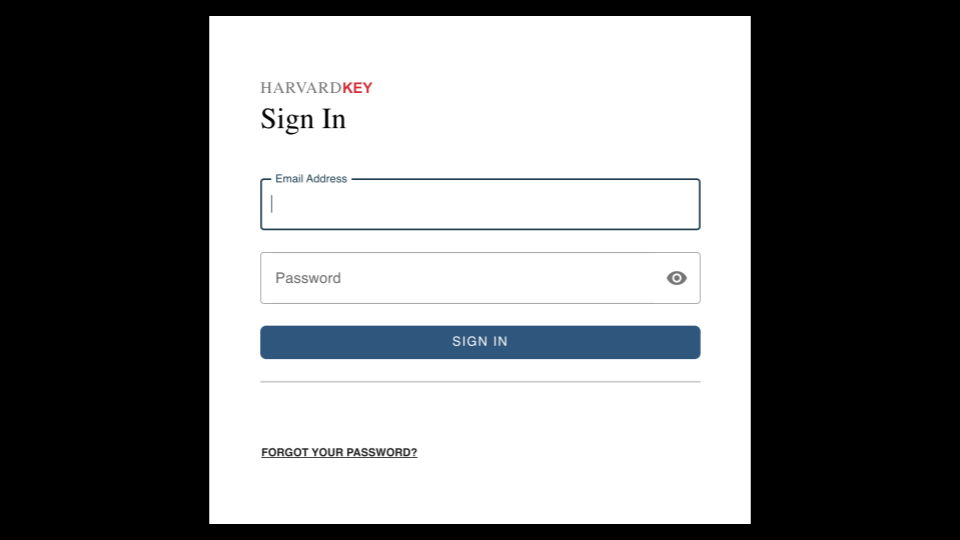

?question marks do above. One of the problems that can arise in real-world applications of SQL is what is called an injection attack. An injection attack is where a malicious actor could input malicious SQL code. - For example, consider a login screen as follows:

- Without the proper protections in our own code, a bad actor could run malicious code. Consider the following:

rows = db.execute("SELECT COUNT(*) FROM users WHERE username = ? AND password = ?", username, password)

Notice that because the ? is in place, validation can be run on favorite before it is blindly accepted by the query.

- You never want to utilize formatted strings in queries as above or blindly trust the user’s input.

- Utilizing the CS50 Library, the library will sanitize and remove any potentially malicious characters.

Summing Up

In this lesson, you learned more syntax related to Python. Further, you learned how to integrate this knowledge with data in the form of flat-file and relational databases. Finally, you learned about SQL. Specifically, we discussed…

- Flat-file databases

- Relational databases

- SQL

- Primary and foreign keys

JOINs- Indexes

- Using SQL in Python

- Race conditions

- SQL injection attacks