CS50 Week01 - Python: Conditionals

- Conditionals

- if Statements

- Control Flow, elif, and else

- or

- and

- Modulo

- Creating Our Own Parity Function

- Pythonic

match- Summing Up

Conditionals

- Conditionals allow you, the programmer, to allow your program to make decisions: As if your program has the choice between taking the left-hand road or the right-hand road based upon certain conditions.

- Built within Python are a set of “operators” that are used to ask mathematical questions.

>and<symbols are probably quite familiar to you.>=denotes “greater than or equal to.”<=denotes “less than or equal to.”==denotes “equals, though do notice the double equal sign! A single equal sign would assign a value. Double equal signs are used to compare variables.!=denotes “not equal to.- Conditional statements compare a left-hand term to a right-hand term.

if Statements

- In your terminal window, type

code compare.py. This will create a brand new file called “compare.” - In the text editor window, begin with the following:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x < y:

print("x is less than y")

Notice how your program takes the input of the user for both x and y, casting them as integers and saving them into their respective x and y variables. Then, the if statement compares x and y. If the condition of x < y is met, the print statement is executed.

ifstatements useboolor boolean values (true or false) to decide whether or not to execute. If the statement ofx > yis true, the compiler will register it astrueand execute the code.

Control Flow, elif, and else

- Further revise your code as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x < y:

print("x is less than y")

if x > y:

print("x is greater than y")

if x == y:

print("x is equal to y")

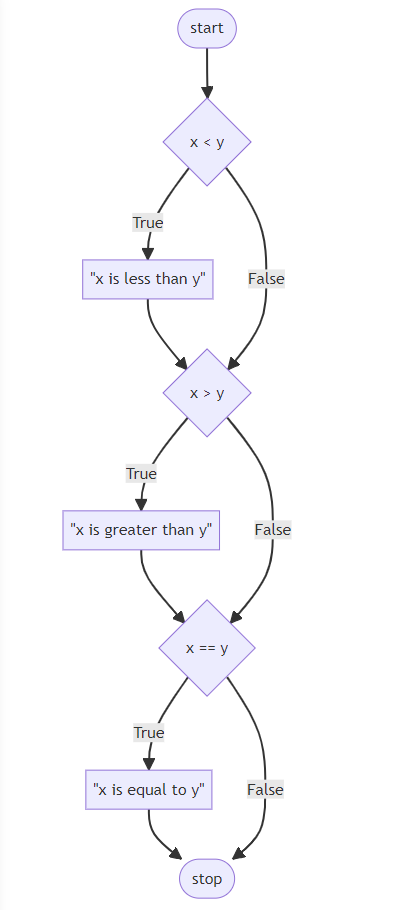

Notice how you are providing a series of if statements. First, the first if statement is evaluated. Then, the second if statement runs its evaluation. Finally, the last if statement runs its evaluation. This flow of decisions is called “control flow.”

- Our code can be represented as follows:

flowchart TD

A([start]) --> B{x < y}

B -- True --> C["#quot;x is less than y#quot;"]

C --> D{x > y}

D -- True --> E["#quot;x is greater than y#quot;"]

E --> F{x == y}

F -- True --> G["#quot;x is equal to y#quot;"]

G --> H([stop])

B -- False --> D

D -- False --> F

F -- False --> H

- This program can be improved by not asking three consecutive questions. After all, not all three questions can have an outcome of

true! Revise your program as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x < y:

print("x is less than y")

elif x > y:

print("x is greater than y")

elif x == y:

print("x is equal to y")

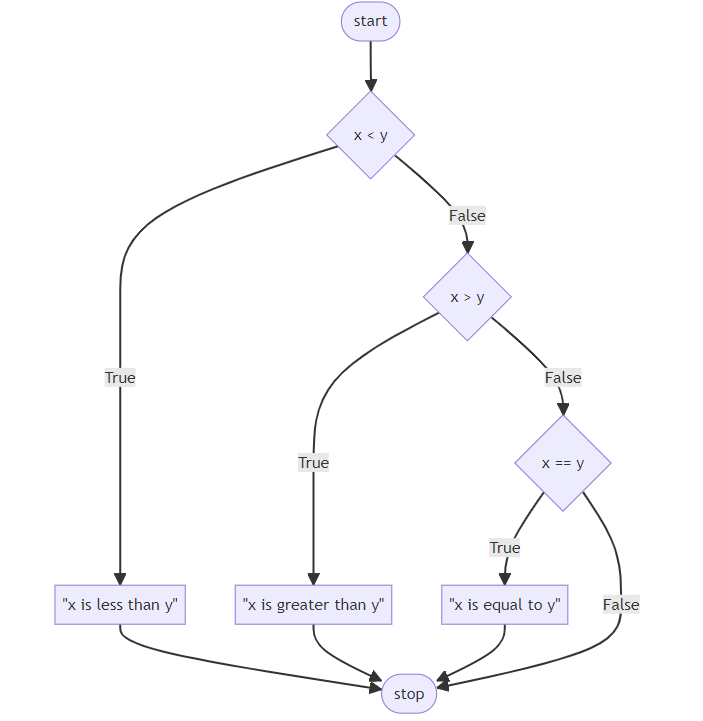

Notice how the use of elif allows the program to make fewer decisions. First, the if statement is evaluated. If this statement is found to be true, all the elif statements will not be run at all. However, if the if statement is evaluated and found to be false, the first elif will be evaluated. If this is true, it will not run the final evaluation.

- Our code can be represented as follows:

flowchart TD

A([start]) --> B{x < y}

B -- True --> C["#quot;x is less than y#quot;"]

B -- False --> D{x > y}

D -- True --> E["#quot;x is greater than y#quot;"]

D -- False --> F{x == y}

F -- True --> G["#quot;x is equal to y#quot;"]

G --> H([stop])

F -- False --> H

C --> H

E --> H

- While your computer may not notice a difference speed-wise between our first program and this revised program, consider how an online server running billions or trillions of these types of calculations each day could definitely be impacted by such a small coding decision.

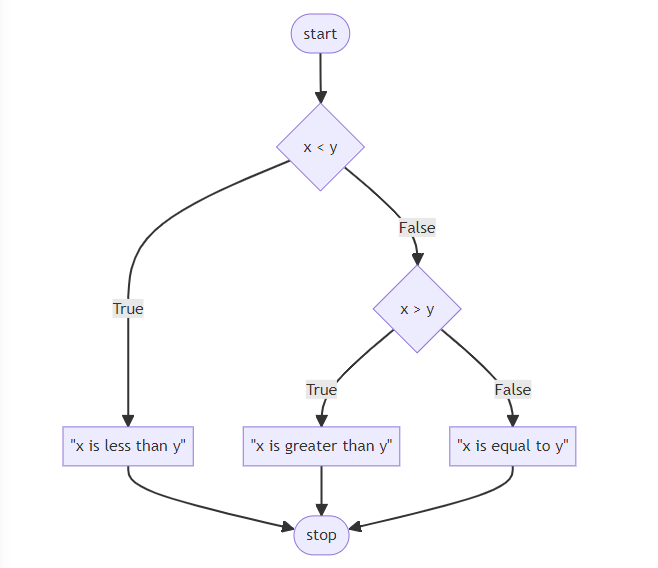

- There is one final improvement we can make to our program. Notice how logically

elif x == yis not a necessary evaluation to run. After all, if logically x is not less than y AND x is not greater than y, x MUST equal y. Therefore, we don’t have to runelif x == y. We can create a “catch-all,” default outcome using anelsestatement. We can revise as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x < y:

print("x is less than y")

elif x > y:

print("x is greater than y")

else:

print("x is equal to y")

Notice how the relative complexity of this program has decreased through our revision.

- Our code can be represented as follows:

flowchart TD

A([start]) --> B{x < y}

B -- True --> C["#quot;x is less than y#quot;"]

B -- False --> D{x > y}

D -- True --> E["#quot;x is greater than y#quot;"]

D -- False --> F["#quot;x is equal to y#quot;"]

F --> G([stop])

C --> G

E --> G

or

orallows your program to decide between one or more alternatives. For example, we could further edit our program as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x < y or x > y:

print("x is not equal to y")

else:

print("x is equal to y")

Notice that the result of our program is the same, but the complexity is decreased. The efficiency of our code is increased.

- At this point, our code is pretty great. However, could the design be further improved? We could further edit our code as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x != y:

print("x is not equal to y")

else:

print("x is equal to y")

Notice how we removed the or entirely and simply asked, “Is x not equal to y?” We ask one and only one question. Very efficient!

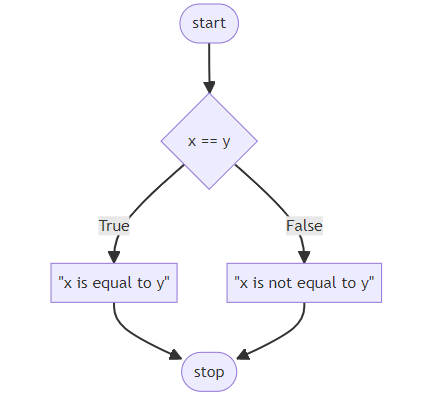

- For the purpose of illustration, we could also change our code as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

y = int(input("What's y? "))

if x == y:

print("x is equal to y")

else:

print("x is not equal to y")

Notice that the == operator evaluates if what is on the left and right are equal to one another. The use of double equal signs is very important. If you use only one equal sign, an error will likely be thrown by the compiler.

- Our code can be illustrated as follows:

flowchart TD

A([start]) --> B{x == y}

B -- True --> C["#quot;x is equal to y#quot;"]

B -- False --> E["#quot;x is not equal to y#quot;"]

C --> F([stop])

E --> F

and

- Similar to

or,andcan be used within conditional statements. - Execute in the terminal window

code grade.py. Start your new program as follows:

score = int(input("Score: "))

if score >= 90 and score <= 100:

print("Grade: A")

elif score >=80 and score < 90:

print("Grade: B")

elif score >=70 and score < 80:

print("Grade: C")

elif score >=60 and score < 70:

print("Grade: D")

else:

print("Grade: F")

Notice that by executing python grade.py, you will be able to input a score and get a grade. However, notice how there is potential for bugs.

- Typically, we do not want to ever trust our users to input the correct information. We could improve our code as follows:

score = int(input("Score: "))

if 90 <= score <= 100:

print("Grade: A")

elif 80 <= score < 90:

print("Grade: B")

elif 70 <= score < 80:

print("Grade: C")

elif 60 <= score < 70:

print("Grade: D")

else:

print("Grade: F")

Notice how Python allows you to chain together the operators and conditions in a way quite uncommon to other programming languages.

- Still, we can further improve our program:

score = int(input("Score: "))

if score >= 90:

print("Grade: A")

elif score >= 80:

print("Grade: B")

elif score >= 70:

print("Grade: C")

elif score >= 60:

print("Grade: D")

else:

print("Grade: F")

Notice how the program is improved by asking fewer questions. This makes our program easier to read and far more maintainable in the future.

- You can learn more in Python’s documentation on control flow.

Modulo

- In mathematics, parity refers to whether a number is either even or odd.

- The modulo

%operator in programming allows one to see if two numbers divide evenly or divide and have a remainder. - For example, 4 % 2 would result in zero, because it evenly divides. However, 3 % 2 does not divide evenly and would result in a number other than zero!

- In the terminal window, create a new program by typing

code parity.py. In the text editor window, type your code as follows:

x = int(input("What's x? "))

if x % 2 == 0:

print("Even")

else:

print("Odd")

Notice how our users can type in any number 1 or greater to see if it is even or odd.

Creating Our Own Parity Function

- As discussed in Lecture 0, you will find it useful to create a function of your own!

- We can create our own function to check whether a number is even or odd. Adjust your code as follows:

def main():

x = int(input("What's x? "))

if is_even(x):

print("Even")

else:

print("Odd")

def is_even(n):

if n % 2 == 0:

return True

else:

return False

main()

Notice that our if statement is_even(x) works even though there is no operator there. This is because our function returns a bool (or boolean), true or false, back to the main function. The if statement simply evaluates whether or not is_even of x is true or false.

Pythonic

- In the programming world, there are types of programming that are called “Pythonic” in nature. That is, there are ways to program that are sometimes only seen in Python programming. Consider the following revision to our program:

def main():

x = int(input("What's x? "))

if is_even(x):

print("Even")

else:

print("Odd")

def is_even(n):

return True if n % 2 == 0 else False

main()

Notice that this return statement in our code is almost like a sentence in English. This is a unique way of coding only seen in Python.

- We can further revise our code and make it more and more readable:

def main():

x = int(input("What's x? "))

if is_even(x):

print("Even")

else:

print("Odd")

def is_even(n):

return n % 2 == 0

main()

Notice that the program will evaluate what is happening within the n % 2 == 0 as either true or false and simply return that to the main function.

match

- Similar to

if,elif, andelsestatements,matchstatements can be used to conditionally run code that matches certain values. - Consider the following program:

name = input("What's your name? ")

if name == "Harry":

print("Gryffindor")

elif name == "Hermione":

print("Gryffindor")

elif name == "Ron":

print("Gryffindor")

elif name == "Draco":

print("Slytherin")

else:

print("Who?")

Notice the first three conditional statements print the same response.

- We can improve this code slightly with the use of the

orkeyword:

name = input("What's your name? ")

if name == "Harry" or name == "Hermione" or name == "Ron":

print("Gryffindor")

elif name == "Draco":

print("Slytherin")

else:

print("Who?")

Notice the number of elif statements has decreased, improving the readability of our code.

- Alternatively, we can use

matchstatements to map names to houses. Consider the following code:

name = input("What's your name? ")

match name:

case "Harry":

print("Gryffindor")

case "Hermione":

print("Gryffindor")

case "Ron":

print("Gryffindor")

case "Draco":

print("Slytherin")

case _:

print("Who?")

Notice the use of the _ symbol in the last case. This will match with any input, resulting in similar behavior as an else statement.

- A match statement compares the value following the

matchkeyword with each of the values following thecasekeywords. In the event a match is found, the respective indented code section is executed, and the program stops the matching. - We can improve the code:

name = input("What's your name? ")

match name:

case "Harry" | "Hermione" | "Ron":

print("Gryffindor")

case "Draco":

print("Slytherin")

case _:

print("Who?")

Notice, the use of the single vertical bar |. Much like the or keyword, this allows us to check for multiple values in the same case statement.

Summing Up

You now have the power within Python to use conditional statements to ask questions and have your program take action accordingly. In this lecture, we discussed…

- Conditionals;

ifStatements;- Control flow,

elif, andelse; or;and;- Modulo;

- Creating your own function;

- Pythonic coding;

- and

match.