CS50 Week07 - Python: Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions

- Regular expressions or “regexes” will enable us to examine patterns within our code. For example, we might want to validate that an email address is formatted correctly. Regular expressions will enable us to examine expressions in this fashion.

- To begin, type

code validate.pyin the terminal window. Then, code as follows in the text editor:

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if "@" in email:

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that strip will remove whitespace at the beginning or end of the input. Running this program, you will see that as long as an @ symbol is inputted, the program will regard the input as valid.

- You can imagine, however, that one could input

@@alone and the input could be regarded as valid. We could regard an email address as having at least one@and a.somewhere within it. Modify your code as follows:

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if "@" in email and "." in email:

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that while this works as expected, our user could be adversarial, typing simply @. would result in the program returning valid.

- We can improve the logic of our program as follows:

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

username, domain = email.split("@")

if username and "." in domain:

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice how the strip method is used to determine if username exists and if . is inside the domain variable. Running this program, a standard email address typed in by you could be considered valid. Typing in malan@harvard alone, you’ll find that the program regards this input as invalid.

- We can be even more precise, modifying our code as follows:

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

username, domain = email.split("@")

if username and domain.endswith(".edu"):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice how the endswith method will check to see if domain contains .edu. Still, however, a nefarious user could still break our code. For example, a user could type in [email protected] and it would be considered valid.

- Indeed, we could keep iterating upon this code ourselves. However, it turns out that Python has an existing library called

rethat has a number of built-in functions that can validate user inputs against patterns. - One of the most versatile functions within the library

reissearch. - The

searchlibrary follows the signaturere.search(pattern, string, flags=0). Following this signature, we can modify our code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search("@", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice this does not increase the functionality of our program at all. In fact, it is somewhat a step back.

- We can further our program’s functionality. However, we need to advance our vocabulary around

validation. It turns out that in the world of regular expressions there are certain symbols that allow us to identify patterns. At this point, we have only been checking for specific pieces of text like@. It so happens that many special symbols can be passed to the compiler for the purpose of engaging in validation. A non-exhaustive list of those patterns is as follows:

. any character except a new line

* 0 or more repetitions

+ 1 or more repetitions

? 0 or 1 repetition

{m} m repetitions

{m,n} m-n repetitions

- Implementing this inside of our code, modify yours as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(".+@.+", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that we don’t care what the username or domain is. What we care about is the pattern. .+ is used to determine if anything is to the left of the email address and if anything is to the right of the email address. Running your code, typing in malan@, you’ll notice that the input is regarded as invalid as we would hope.

- Had we used a regular expression

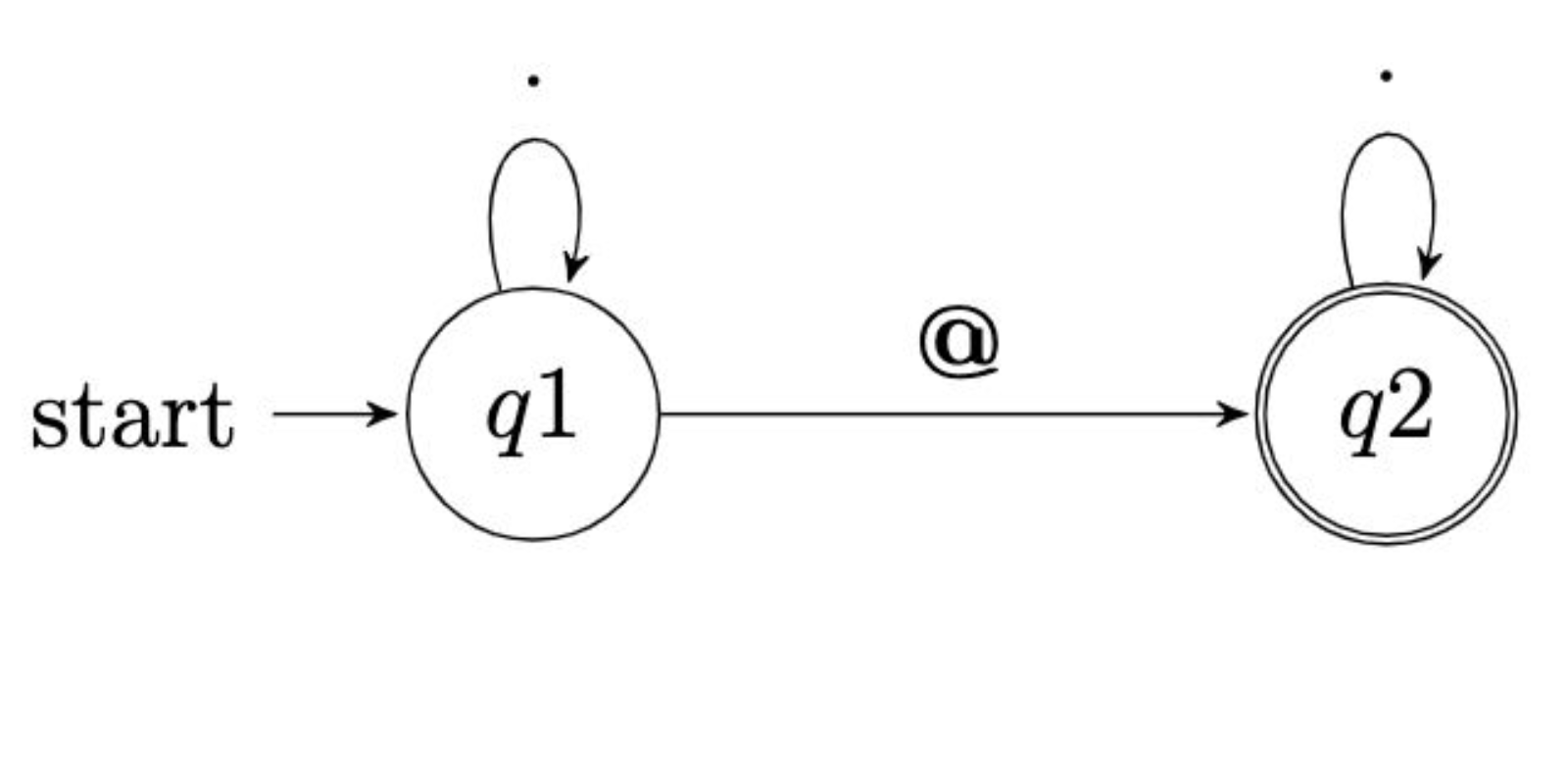

.*@.*in our code above, you can visualize this as follows:

Notice the depiction of the state machine of our regular expression. On the left, the compiler begins evaluating the statement from left to right. Once we reach q1 or question 1, the compiler reads time and time again based on the expression handed to it. Then, the state is changed looking now at q2 or the second question being validated. Again, the arrow indicates how the expression will be evaluated time and time again based upon our programming. Then, as depicted by the double circle, the final state of state machine is reached.

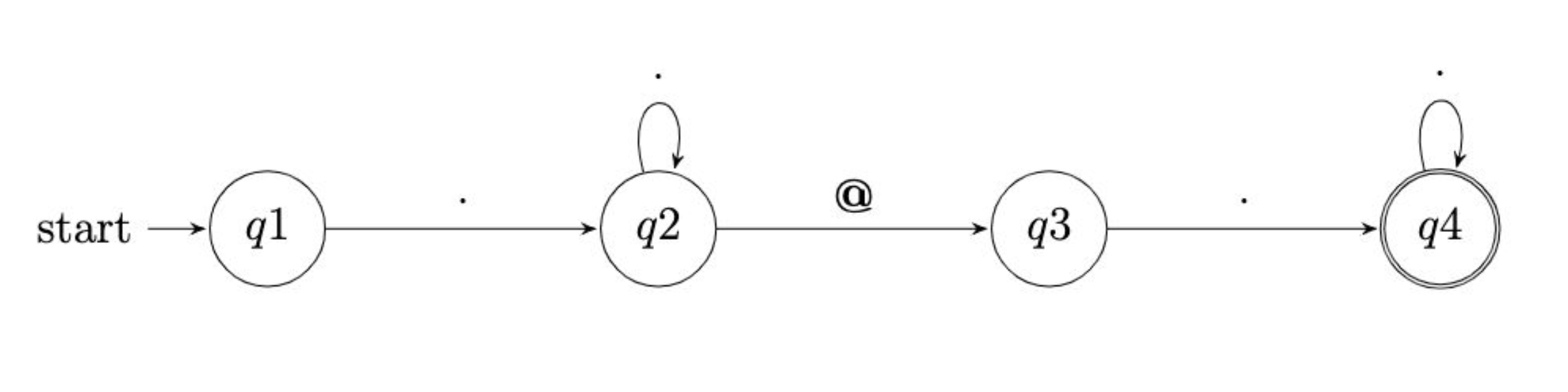

- Considering the regular expression we used in our code,

.+@.+, you can visualize it as follows:

Notice how q1 is any character provided by the user, including ‘q2’ as 1 or more repetitions of characters. This is followed by the ‘@’ symbol. Then, q3 looks for any character provided by the user, including q4 as 1 or more repetitions of characters.

- The

reandre.searchfunctions and ones like them look for patterns. - Continuing our improvement of this code, we could improve our code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(".+@.+.edu", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice, however, that one could type in malan@harvard?edu and it could be considered valid. Why is this the case? You might recognize that in the language of validation, a . means any character!

- We can modify our code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r".+@.+\.edu", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice how we utilize the “escape character” or \ as a way of regarding the . as part of our string instead of our validation expression. Testing your code, you will notice that [email protected] is regarded as valid, where malan@harvard?edu is invalid.

- Now that we’re using escape characters, it’s a good time to introduce “raw strings”. In Python, raw strings are strings that don’t format special characters—instead, each character is taken at face-value. Imagine

\n, for example. We’ve seen in an earlier lecture how, in a regular string, these two characters become one: a special newline character. In a raw string, however,\nis treated not as\n, the special character, but as a single\and a singlen. Placing anrin front of a string tells the Python interpreter to treat the string as a raw string, similar to how placing anfin front of a string tells the Python interpreter to treat the string as a format string:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^.+@.+\.edu$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Now we’ve ensured the Python interpreter won’t treat \. as a special character. Instead, simply as a \ followed by a .—which, in regular expression terms, means matching a literal “.”.

- You can imagine still how our users could create problems for us! For example, you could type in a sentence such as

My email address is [email protected].and this whole sentence would be considered valid. We can be even more precise in our coding. - It just so happens we have more special symbols at our disposal in validation:

^ matches the start of the string

$ matches the end of the string or just before the newline at the end of the string

- We can modify our code using our added vocabulary as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^.+@.+\.edu$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice this has the effect of looking for this exact pattern matching to the start and end of the expression being validated. Typing in a sentence such as My email address is [email protected]. now is regarded as invalid.

- We propose we can do even better! Even though we are now looking for the username at the start of the string, the

@symbol, and the domain name at the end, we could type in as many@symbols as we wish!malan@@@harvard.eduis considered valid! - We can add to our vocabulary as follows:

[] set of characters

[^] complementing the set

- Using these newfound abilities, we can modify our expression as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^[^@]+@[^@]+\.edu$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that ^ means to match at the start of the string. All the way at the end of our expression, $ means to match at the end of the string. [^@]+ means any character except an @. Then, we have a literal @. [^@]+\.edu means any character except an @ followed by an expression ending in .edu. Typing in malan@@@harvard.edu is now regarded as invalid.

- We can still improve this regular expression further. It turns out there are certain requirements for what an email address can be! Currently, our validation expression is far too accomodating. We might only want to allow for characters normally used in a sentence. We can modify our code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^[a-zA-Z0-9_]+@[a-zA-Z0-9_]+\.edu$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that [a-zA-Z0-9_] tells the validation that characters must be between a and z, between A and Z, between 0 and 9 and potentially include an _ symbol. Testing the input, you’ll find that many potential user mistakes can be indicated.

- Thankfully, common patterns have been built into regular expressions by hard-working programmers. In this case, you can modify your code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^\w+@\w+\.edu$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that \w is the same as [a-zA-Z0-9_]. Thanks, hard-working programmers!

- Here are some additional patterns we can add to our vocabulary:

\d decimal digit

\D not a decimal digit

\s whitespace characters

\S not a whitespace character

\w word character, as well as numbers and the underscore

\W not a word character

- Now, we know that there are not simply

.eduemail addresses. We could modify our code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^\w+@\w.+\.(com|edu|gov|net|org)$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice that the | has the impact of an or in our expression.

- Adding even more symbols to our vocabulary, here are some more to consider:

A|B either A or B

(...) a group

(?:...) non-capturing version

Case Sensitivity

- To illustrate how you might address issues around case sensitivity, where there is a difference between

EDUandeduand the like, let’s rewind our code to the following:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^\w+@\w+\.edu$", email):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice how we have removed the | statements provided previously.

- Recall that within the

re.searchfunction, there is a parameter forflags. - Some built-in flag variables are:

re.IGNORECASE

re.MULTILINE

re.DOTALL

Consider how you might use these in your code.

- Therefore, we can change our code as follows.

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^\w+@\w+\.edu$", email, re.IGNORECASE):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice how we added a third parameter re.IGNORECASE. Running this program with [email protected], the input is now considered valid.

- Consider the following email address

[email protected]. Using our code above, this would be considered invalid. Why might that be? - Since there is an additional

., the program considers this invalid. - It turns out that we can, looking at our vocabulary from before, we can group together ideas.

A|B either A or B

(...) a group

(?:...) non-caputuring version

- We can modify our code as follows:

import re

email = input("What's your email? ").strip()

if re.search(r"^\w+@(\w+\.)?\w+\.edu$", email, re.IGNORECASE):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

Notice how the (\w+\.)? communicates to the compiler that this new expression can be there once or not at all. Hence, both [email protected] and [email protected] are considered valid.

- Interestingly enough, the edits we have done so far to our code do not fully encompass all the checking that could be done to ensure a valid email address. Indeed, here is the full expression that one would have to type to ensure that a valid email is inputted:

^[a-zA-Z0-9.!#$%&'*+\/=?^_`{|}~-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9](?:[a-zA-Z0-9-]{0,61}[a-zA-Z0-9])?(?:\.[a-zA-Z0-9](?:[a-zA-Z0-9-]{0,61}[a-zA-Z0-9])?)*$

-

There are other functions within the

relibrary you might find useful.re.matchandre.fullmatchare ones you might find exceedingly useful. -

You can learn more in Python’s documentation of re.

Cleaning Up User Input

- You should never expect your users to always follow your hopes for clean input. Indeed, users will often violate your intentions as a programmer.

- There are ways to clean up your data.

- In the terminal window, type

code format.py. Then, in the text-editor, code as follows:

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice that we have created, essentially, a “hello world” program. Running this program and typing in David, it works well! However, typing in Malan, David notice how the program does not function as intended. How could we modify our program to clean up this input?

- Modify your code as follows.

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

if "," in name:

last, first = name.split(", ")

name = f"{first} {last}"

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice how last, first = name.split(", ") is run if there is a , in the name. Then, the name is standardized as first and last. Running our code, typing in Malan, David, you can see how this program does clean up at least one scenario where a user types in something unexpected.

- You might notice that typing in

Malan,Davidwith no space causes the compiler to throw an error. Since we now know some regular expression syntax, let’s apply that to our code:

import re

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

matches = re.search(r"^(.+), (.+)$", name)

if matches:

last, first = matches.groups()

name = first + " " + last

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice that re.search can return a set of matches that are extracted from the user’s input. If matches are returned by re.search. Running this program, typing in David Malan notice how the if condition is not run and the name is returned. If you run the program by typing Malan, David, the name is also returned properly.

- It just so happens that we can request specific groups back using

matches.group. We can modify our code as follows:

import re

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

matches = re.search(r"^(.+), (.+)$", name)

if matches:

name = matches.group(2) + " " + matches.group(1)

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice how, in this implementation, group is not plural (there is no s).

- Our code can be further tightened as follows:

import re

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

matches = re.search(r"^(.+), (.+)$", name)

if matches:

name = matches.group(2) + " " + matches.group(1)

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice how group(2) and group(1) are concatenated together with a space. The first group is that which is left of the comma. The second group is that which is right of the comma.

- Recognize still that typing in

Malan,Davidwith no space will still break our code. Therefore, we can make the following modification:

import re

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

matches = re.search(r"^(.+), *(.+)$", name)

if matches:

name = matches.group(2) + " " + matches.group(1)

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice the addition of the * in our validation statement. This code will now accept and properly process Malan,David. Further, it will properly handle ` David,Malan with many spaces in front of David`.

- It is very common to utilize

re.searchas we have in the previous examples, wherematchesis on a line of code after. However, we can combine these statements:

import re

name = input("What's your name? ").strip()

if matches := re.search(r"^(.+), *(.+)$", name):

name = matches.group(2) + " " + matches.group(1)

print(f"hello, {name}")

Notice how we combine two lines of our code. The walrus := operator assigns a value from right to left and allows us to ask a boolean question at the same time. Turn your head sideways and you’ll see why this is called a walrus operator.

- You can learn more in Python’s documentation of re.

Extracting User Input

- So far, we have validated the user’s input and cleaned up the user’s input.

- Now, let’s extract some specific information from user input. In the terminal window, type

code twitter.pyand code as follows in the text editor window:

url = input("URL: ").strip()

print(url)

Notice that if we type in https://twitter.com/davidjmalan, it shows exactly what the user typed. However, how would we be able to extract just the username and ignore the rest of the URL?

- You can imagine how we would simply be able to get rid of the beginning of the standard Twitter URL. We can attempt this as follows:

url = input("URL: ").strip()

username = url.replace("https://twitter.com/", "")

print(f"Username: {username}")

Notice how the replace method allows us to find one item and replace it with another. In this case, we are finding part of the URL and replacing it with nothing. Typing in the full URL https://twitter.com/davidjmalan, the program effectively outputs the username. However, what are some shortcomings of this current program?

- What if the user simply typed

twitter.cominstead of including thehttps://and the like? You can imagine many scenarios where the user may input or neglect to input parts of the URL that would create strange output by this program. To improve this program, we can code as follows:

url = input("URL: ").strip()

username = url.removeprefix("https://twitter.com/")

print(f"Username: {username}")

Notice how we utilize the removeprefix method. This method will remove the beginning of a string.

- Regular expressions simply allow us to succinctly express the patterns and goals.

- Within the

relibrary, there is a method calledsub. This method allows us to substitute a pattern with something else. - The signature of the

submethod is as follows

re.sub(pattern, repl, string, count=0, flags=0)

Notice how pattern refers to the regular expression we are looking for. Then, there is a repl string that we can replace the pattern with. Finally, there is the string that we want to do the substitution on.

- Implementing this method in our code, we can modify our program as follows:

import re

url = input("URL: ").strip()

username = re.sub(r"https://twitter.com/", "", url)

print(f"Username: {username}")

Notice how executing this program and inputting https://twitter.com/davidjmalan produces the correct outcome. However, there are some problems still present in our code.

- The protocol, subdomain, and the possibility that the user inputted any part of the URL after the username are all reasons that this code is still not ideal. We can further address these shortcomings as follows:

import re

url = input("URL: ").strip()

username = re.sub(r"^(https?://)?(www\.)?twitter\.com/", "", url)

print(f"Username: {username}")

Notice how the ^ caret was added to the url. Notice also how the . could be interpreted improperly by the compiler. Therefore, we escape it using a \ to make it \. For the purpose of tolerating both http and https, we add a ? to the end of https?, making the s optional. Further, to accommodate www we add (www\.)? to our code. Finally, just in case the user decides to leave out the protocol altogether, the http:// or https:// is made optional using (https?://).

- Still, we are blindly expecting that what the user inputted a url that, indeed, has a username.

- Using our knowledge of

re.search, we can further improve our code.

import re

url = input("URL: ").strip()

matches = re.search(r"^https?://(www\.)?twitter\.com/(.+)$", url, re.IGNORECASE)

if matches:

print(f"Username:", matches.group(2))

Notice how we are searching for the regular expression above in the string provided by the user. In particular, we are capturing that which appears at the end of the URL using (.+)$ regular expression. Therefore, if the user fails to input a URL without a username, no input will be presented.

- Even further tightening up our program, we can utilize our

:=operator as follows:

import re

url = input("URL: ").strip()

if matches := re.search(r"^https?://(?:www\.)?twitter\.com/(.+)$", url, re.IGNORECASE):

print(f"Username:", matches.group(1))

Notice that the ?: tells the compiler it does not have to capture what is in that spot in our regular expression.

- Still, we can be more explicit to ensure that the username inputted is correct. Using Twitter’s documentation, we can add the following to our regular expression:

import re

url = input("URL: ").strip()

if matches := re.search(r"^https?://(?:www\.)?twitter\.com/([a-z0-9_]+)", url, re.IGNORECASE):

print(f"Username:", matches.group(1))

Notice that the [a-z0-9_]+ tells the compiler to only expect a-z, 0-9, and _ as part of the regular expression. The + indicates that we are expecting one or more characters.

- You can learn more in Python’s documentation of re.

Summing Up

Now, you’ve learned a whole new language of regular expressions that can be utilized to validate, clean up, and extract user input.

- Regular Expressions

- Case Sensitivity

- Cleaning Up User Input

- Extracting User Input